Representation and Resilience in Science Communication

At the inaugural Conference for Emerging Black Academics in STEM, a panel of science communicators spoke about social media, authenticity, and empowerment.

by Julia Ehlert

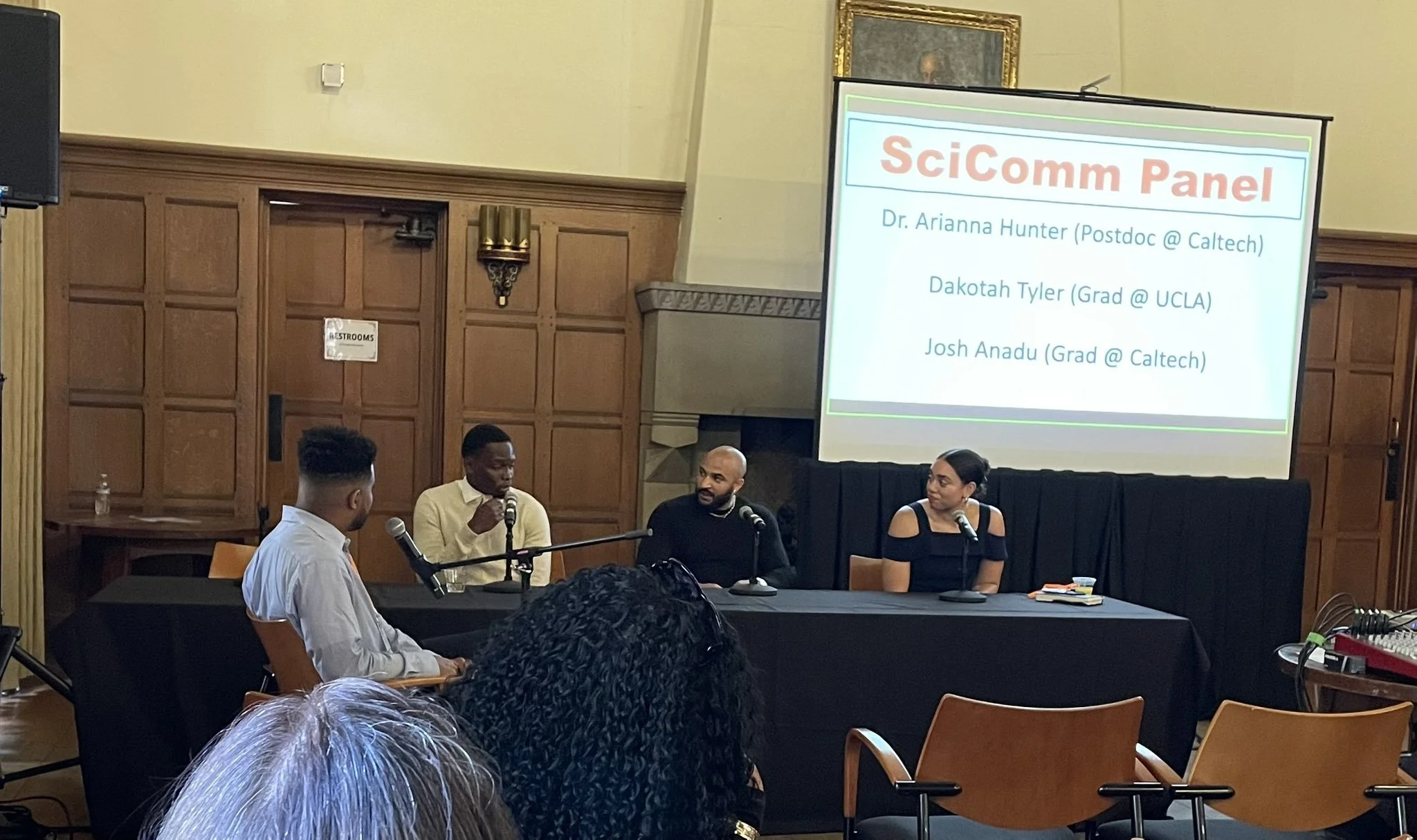

Left to right: Thomas Henning, Josh Anadu, Dakotah Tyler, and Arianne Hunter speak on the science communication panel. Photo: Darla Wolfe

Josh Anadu, a geobiology graduate student at Caltech, usually posts funny science videos on his YouTube channel. But the tenor of his social media changed drastically one day in 2020, when he uploaded a video describing a racist encounter he had while doing geology fieldwork in Missouri.

As an undergraduate at Oklahoma State University, Anadu spent a summer working as a field technician doing geophysical surveys. In the video, he described the first week in his role after experiencing a series of racially tense encounters with locals. Things escalated when he and another Black student realized they were next to a property owned by white supremacists, with racist symbols on full display.

“It’s a thing that happens in geology, unfortunately. I just happened to run into some people in the KKK [Ku Klux Klan]. … I had been working in the field for several months, I went back to my hotel room and I was upset about it, so I made a video about it.”

Anadu spoke about the video and his experiences as a Black scientist and YouTuber while on a science communication (SciComm) panel at the Conference for Emerging Black Academics in STEM (CEBAS) hosted by Caltech on May 12. The panel, moderated by conference co-organizer and Caltech neuroscience graduate student Thomas Henning, also featured Arianne Hunter, Caltech Presidential Postdoctoral Scholar in chemistry, and Dakotah Tyler, an astrophysics graduate student at UCLA.

At the panel, Anadu said he gained several thousand followers after cross posting his video to Twitter. But his newfound audience seemed disinterested in his more positive videos about science and research.

“I felt like it was driving me to do different things or to say different things than I wanted to say. … When I would go back to tweeting the things I enjoy or being happy, it was like crickets—you don’t hear anything. And then if I said something about being a Black scientist, it gets likes and retweets like crazy.”

Anadu said the pressure drove him to leave Twitter and focus instead on creative content on YouTube. His channel, Black Thoughts, features vlogs, guest interviews with other scientists, and comedy videos about science and academia.

“At some point I started doing standup comedy, and people would ask me questions about science and the science I do,” Anadu said. “I thought [making videos] would be a way in which you’re entertaining and not always just talking about science itself, but also bringing in scientists and letting them be themselves.”

Tyler and Hunter also stressed the importance of authenticity and representation in science communication.

“There’s not a lot of Black scientists, and there’s even less Black science communicators,” said Tyler, whose science videos have more than 1 million views across TikTok, Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter. “People have the idea that scientists all look a certain way. I didn’t want to be like any of the science communicators I was exposed to when I grew up. That’s why it’s so important for us to just be ourselves.”

Hunter, who curates a social media presence across Twitter, LinkedIn, and Instagram, echoed the sentiment. “It wasn’t until recently that I started being more authentic on my platform.” She described having two separate Twitter accounts to interact with different users, topics, and content on the site—one for “Black Twitter” and one for “chemistry Twitter.” Hunter explained that her goal was to “merge those two a little bit more” and share content on both accounts that spoke to both elements of her identity.

Asked why she made that change, Hunter shared an experience from when she participated in a Twitter networking panel hosted by a professor in Arizona the week after Samantha Mensah, a UCLA graduate student and prominent Black scientist on Twitter, died by suicide.

“The panel started and no one mentioned her,” Hunter said. “When it came time for me to talk, I just said, ‘I want you guys to know that I’m completely disgusted with everyone that’s on this panel. We need to do better. Sammy is the reason why the majority of us are here and are actually using this space as a network.’”

“Afterwards, I realized they’re so unappreciative of the work that Black and Brown people do, in all spaces of communication. … Everything that we do, it gets colonized. And when I put those things together, it just made me very, very angry. I was like, you know what? You guys are getting the real Ari, you’re getting the activist Ari. Because I’m always activist Ari in real life.”

Tyler also spoke about exclusionary behavior he faced as a Black science communicator.

“I get questioned all the time,” said Tyler. “People telling me to do X or X equation, or do this, or they don’t believe I’m an actual physicist. On like a daily basis, I get these sorts of messages from people. You have to learn to be resilient or it’s gonna drive you crazy.”

The necessity of resilience was a common theme. Each panelist mentioned that it was something that kept them going despite the adversity they faced in science communication and academic spaces.

“Whenever someone tries to drown my voice out, I’m just like, ‘Yeah, no, that’s not happening,’” said Hunter.

“I actually get dopamine hits every time somebody rejects me, or I fail, or something like that,” added Tyler. “It really drives me and propels me to do better.”

At the same time, the panelists shared their appreciation for science communication as a meaningful, accessible way to inspire passion for science.

“I was introduced to science through SciComm,” Hunter said. “I come from a low socioeconomic background. I didn't have that great of a public school education in Oklahoma.” Hunter described watching science communicators on television as a child and mimicking them before eventually becoming a chemist.

For Tyler, documentaries were what drew him to the study of astrophysics and inspired him to start making videos about the cosmos.

“I just realized that we lived in this infinite universe, right? And we all get so locked into our individual perspectives of the small lives that we live and people we know in one city, in one state, the whole country. And there's trillions of planets. I was just really curious to sort of pursue that [sense of awe] and then to share that.”